Bulstrode Camp – a detailed history

These details are taken from The Gerrards Cross Town Council pages here

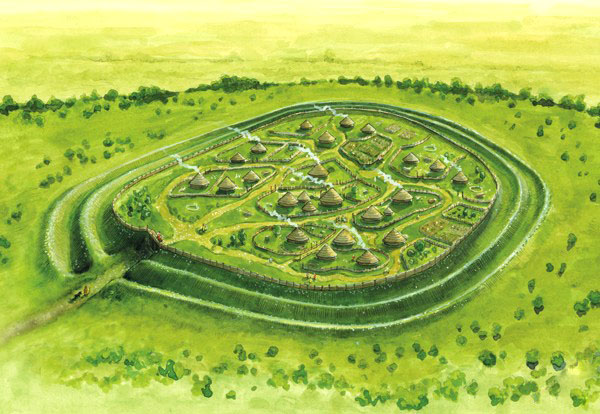

Bulstrode Camp is a good example of a large multivallate hillfort. The definition of a large multivallate hillfort is a fortified enclosure, located on a hill, and defined by 2 or more lines of concentric earthworks, which demarcate an internal area of between 5 and 85 hectares.

The Camp is the largest hillfort in Buckinghamshire, covering an area of 10.67 hectares (26.38 acres). It would originally have stood on an unwooded plateau and been visible from some distance, dominating the surrounding countryside. The name Bulstrode, first recorded as ‘Burstrod’, derives from the Anglo-Saxon for “the marsh belonging to the fort”.

The Camp’s defences consist of a double rampart with inner and outer ditches, except on the steep western side (Crab Hill) where the outer bank and ditch are not visible. The steepness of Crab Hill may have been one of the reasons why the Camp was situated where it is.

The total defensive system is about 27 metres (89 feet) wide. The inner rampart reaches a maximum height of 3.7 metres (12 feet) above its ditch, while the outer rampart reaches a maximum height of 1.8-2.1 metres (6-7 feet) above its ditch. The ramparts have been eroded and would certainly have been higher in antiquity. Serious levelling of the earthworks has occurred on the eastern side, just north of the footpath. This levelling looks as if it is connected with an avenue heading towards Bulstrode House shown on the 1686 Bulstrode estate map. An estate tradition claims that one of the Dukes of Portland leveled the rampart at the other, western, end of this avenue as well.

Most large multivallate hillforts had two entrances. There are five modern entrances to the Camp, but none of them is necessarily original.

When was the Camp constructed?

Until the late nineteenth-century such fortifications were believed to be Roman, Saxon or Danish rather than British. Indeed the Camp was described as Saxon in a London Underground publication of c. 1922. Today we know that most hillforts were built between the Late Bronze Age (after 1200 BC) and the Middle Iron Age (before 100 BC), with a high point of construction and occupation in the Early Iron Age (c. 600-300 BC). Large multivallate forts began appearing around 600 BC, and in some cases continued being used until the mid-1st century AD. Some were reoccupied in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD.

It is impossible to give a precise date for the construction of the Camp, and in any case it may very well have evolved over time. Small amounts of pottery found by archaeological excavators in 1924 were identified as being of Early Iron Age date. Bronze objects are also said to have been found in the vicinity, which may suggest Bronze Age (c. 2000-750 BC) occupation of the site.

Hillforts can be of two types, earlier ‘wall-and-fill’ forts and later ‘dump construction’ forts. The earlier method involved constructing the ramparts using stone or timber revetments. The later method simply involved creating an unsupported rampart from the material removed from the ditch. The limited archaeological excavations of 1924 suggested that the Camp has a ‘dump construction’ rampart and that it dates from a single period. This, and the fact that the Camp is multivallate, suggest that it is not very early. Bambi Stainton, an authority on this period and a contributor to Branigan’s The Archaeology of the Chilterns (1994), is reported as dating it to c. 400 BCE, drawing parallels with Ivinghoe Beacon hillfort, where material of this date has been found.

Prehistoric Gerrards Cross

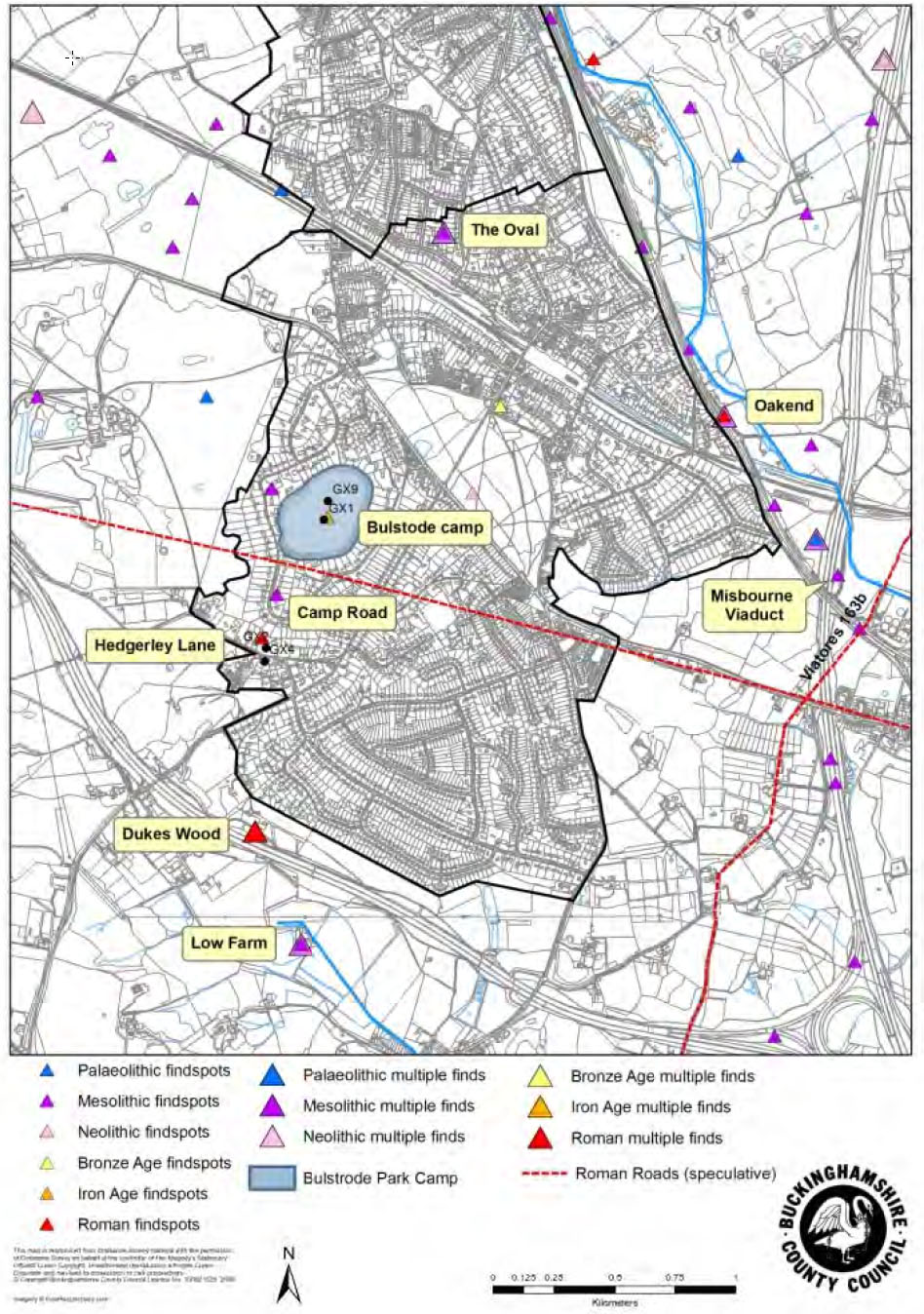

The people who built the Camp were not Gerrards Cross’s first residents. Palaeolithic (pre-8000 BC) hand axes have been found at Bulstrode Park and along the A40. In 1966 and 1967 four Mesolithic (c. 8000-4000 BC) sites were found along the A413. Two were excavated and an Early Mesolithic (pre-6750 BC) date was suggested. When the M25 was being constructed a Late Mesolithic site was found, with artefacts giving a radiocarbon date of 4150 BC ± 120 years.

Recently geophysical evidence has also been found suggesting that there may be the remains of a Neolithic (c. 3100-2000 BC) or Bronze Age long barrow in the south-west quadrant of the Camp itself. If this is the case this burial mound predates the Camp and suggests that the site was of importance to human beings significantly before the fortification was built. Other long barrows found in the Chilterns have dated from the Early Neolithic (c. 3100-2600 BC).

What was the Camp’s function?

Not only are we not entirely sure about when the Camp was built, we do not know exactly what it was built for. It has been suggested that the camp was constructed where it is because it guarded a prehistoric route along the Misbourne Valley, or that it was intended as “a summer camp for stock movement or control”, or that it was “a meeting point for tribal or family groups in the Chiltern and middle Thames area”.

Views about hillforts have changed in recent years. As Stewart Bryant, County Archaeologist for Hertfordshire, says in his chapter on the late Bronze and Iron Ages in Branigan’s The Archaeology of the Chilterns:

“In the past explanations have tended to view hillforts as residences of the tribal chiefs or as defended towns and have also emphasised their role in warfare. These explanations have largely proved to be unsatisfactory, and more recent theories have concentrated on their role in the local social and economic system particularly as centres for the storage and redistribution of agricultural produce. It now seems likely that one of the main functions of hillforts was to serve as secure centres for the storage of grain and stock gathered from the smaller farming settlements in the surrounding territory”.

Hillforts may have served as refuges in times of danger, but this was probably a secondary role. Another authority points out that there is “good evidence that forts were intended by their builders as sites for permanent human settlement, although in some major forts this settlement may not have occupied the whole of the interior area, and may not in fact have lasted for very long”. Intensive occupation was probably only seasonal. Hillforts may also have served as centres for ceremonial and religious activities. It has also been suggested that hillforts were status symbols.

Hillforts may have served as refuges in times of danger, but this was probably a secondary role. Another authority points out that there is “good evidence that forts were intended by their builders as sites for permanent human settlement, although in some major forts this settlement may not have occupied the whole of the interior area, and may not in fact have lasted for very long”. Intensive occupation was probably only seasonal. Hillforts may also have served as centres for ceremonial and religious activities. It has also been suggested that hillforts were status symbols.

Modern research suggests that chieftains lived in smaller ‘ringworks’ and that most of the population lived in farms and hamlets. The closest known Iron Age settlements to the Camp were some 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) away in the lowland Colne Valley.

The Camp after the Roman invasion

There is no evidence that the Camp was occupied after the arrival of the Romans. However there were Roman pottery kilns nearby, at Fulmer and Hedgerley. One was discovered at Wapseys Wood in 1935, and several others have been found since 1963. They supplied nearby villas, but not major towns, and may have been seasonal operations.

There were two early modern avenues on the Camp by 1686, one going towards Bulstrode House and one to a house and buildings that once existed in the northwest corner. The Camp may have been ploughed in the Middle Ages, and was certainly ploughed during the Second World War. It was also used as a practice landing ground for Westland Lysander aircraft, the machines used to land and pick up SOE agents in occupied countries.

There were two early modern avenues on the Camp by 1686, one going towards Bulstrode House and one to a house and buildings that once existed in the northwest corner. The Camp may have been ploughed in the Middle Ages, and was certainly ploughed during the Second World War. It was also used as a practice landing ground for Westland Lysander aircraft, the machines used to land and pick up SOE agents in occupied countries.

The Camp today

Most of the Camp was acquired by Gerrards Cross Parish Council in the early 1950s “for preservation as an Ancient Monument and a Public Open Space for the rest and recreation of the Parishioners”. Seventeen houses also have parts of the fortifications in their gardens.

Most of the Camp was acquired by Gerrards Cross Parish Council in the early 1950s “for preservation as an Ancient Monument and a Public Open Space for the rest and recreation of the Parishioners”. Seventeen houses also have parts of the fortifications in their gardens.

The Camp is a Scheduled Site, listed under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979. No works of any kind affecting the site can be carried out without the prior consent of the Secretary of State for the Environment. The Secretary of State is required to consult the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission before giving any decision that would affect the site. The County Field Archaeologist would also normally be notified.

It is an offence for any person to use a metal detector on the site without the consent of the Secretary of State. Digging on the Camp is not permitted, and neither is the lighting of fires.

Finds, excavations and discoveries at the Camp

Various prehistoric items are supposed to have been found around the Camp over the years. These include a number of metal objects, including a bronze pot, all now lost. A few flint spearheads and a non-local grinding stone have also been found.

The Camp has been excavated twice, once in summer 1924 and once in 1969. The 1924 excavation, by Cyril Fox and L.C.G. Clarke (click here for original report), was significantly hindered by rain. Overall it found little of interest. Excavation of the ramparts suggested they were made “solely of the gravel and sand removed from the ditch”, i.e. dump construction. If Fox and Clarke are correct in thinking that “there was nothing to indicate that the rampart had been added to since its original construction” then the fortification was created in a single phase. A hearth of pebbles was found in the south-east corner, and a couple of pieces of pottery, “apparently pre-Roman”. Another piece, “certainly pre-Roman, and probably Early Iron Age”, was found at Crab Hill. Fox and Clarke concluded that “the fortress was never a settlement, but merely a camp of refuge”. Because of the size of the defences they also rejected the possibility that the Camp was “merely an enclosure for cattle”.

Another limited excavation of Bulstrode Camp took place in 1969. It was motivated less by academic curiosity than by Eton Rural District Council’s need to install a sewer. The operations were observed by S.A. Moorhouse of the Ancient Monuments Department, Ministry of Public Buildings and Works, and by Gerrards Cross and Chalfont St. Peter Local History Society. The excavators were able to record the stratification of the bank and, despite being hampered by water, managed to reach the floor of a ditch, unlike their 1924 predecessors. They also found two post-holes in the interior and evidence of a previously undiscovered inner ditch, but no objects or unusual features were uncovered. The excavators concluded, as Fox and Clarke had done in 1924, that the Camp was “rather a camp of refuge for intermittent occupation and not a permanent settlement” (Records of Bucks, Vol. 18 p. 324).

A geophysical survey between March and November 2002 detected “a number of possible prehistoric anomalies”, mostly around the margins in the northern part of the site. Since these anomalies are circular and between 9 and 16 metres across it is possible that they are round houses. The survey also found evidence of what might be a 60 by 15 metre Neolithic or Bronze Age long barrow (John Gover – Bulstrode ‘Iron Age’ Camp Gerrards Cross: A Site of Many Periods, in Journal of Chess Valley Archaeological & Historical Society, 2003).